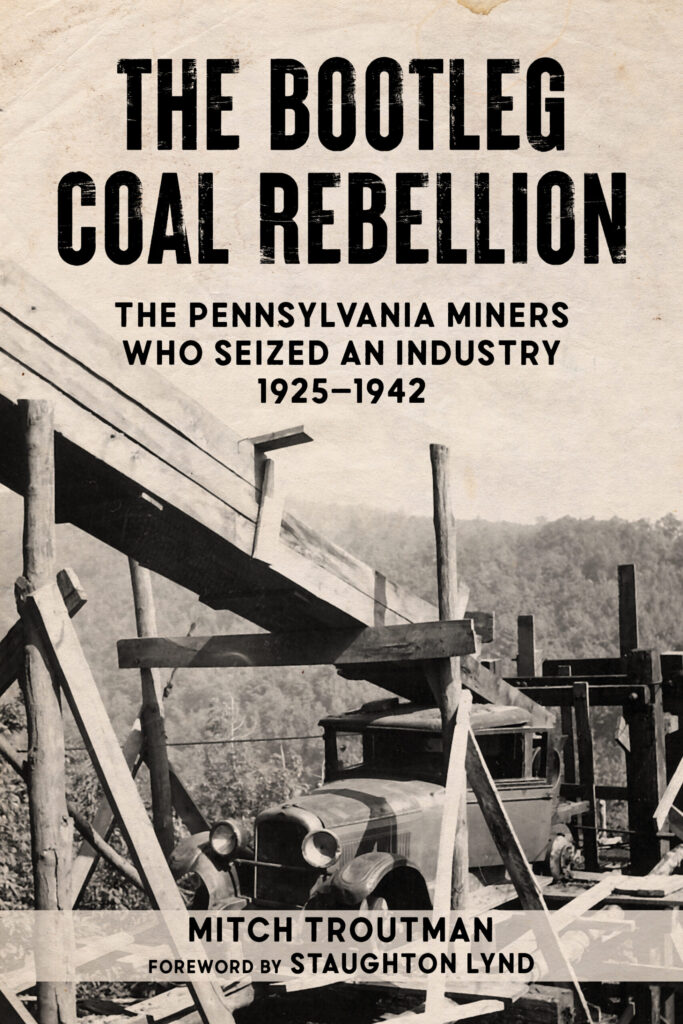

THE BOOTLEG COAL REBELLION: The Pennsylvania Miners Who Seized an Industry 1925-1942

by Mitch Troutman

PM Press

(www.pmpress.org)

2022, 274 pp., $24.95

ISBN 978-1-62963-933-8

Click Here to Purchase

My parents grew up in what sounded to me, when we visited, like “the cold regions” on our hours-long drive many weekends up Rt. 61 to the towns of Shenandoah and Sheppton in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. My dad’s immediate family consisted of bootleg coal miners. I remember many discussions about black lung. I remember Mom talking about how hard it was to clean the coal dust off of Dad. About his potential spine and other issues in the brutal life down under the ground, digging for anthracite (and Dad’s lengthy explanations of the difference between that and bituminous coal).

Importantly, Dad told us the story of why he left his family’s bootlegging coal operation when an accident happened, a horrible cave-in that killed a man and his son. I don’t think Dad wanted to die that way.

After the coal-mining stint, Dad was content to join the Army Air Corps during World War II, take advantage of the GI Bill, go to college and get the heck out of Schuylkill County.

So there was a lot of nostalgia reading THE BOOTLEG COAL REBELLION, an exhaustive collection of court and newspaper records and personal accounting of the strife and strikes bootleggers faced.

Why bootleg? Simple: it’s a business decision when a larger company, such as Reading Anthracite, decides it is more cost-effective and boosts coal prices after they shut commercial company mines down, leaving many miners out of work, uncaring about their welfare, leaving them to fend for themselves. And fend they did, digging for coal en masse.

According to REBELLION, most bootleg mining, about two-thirds, took place in Schuylkill County. In 1936, for example, bootleggers produced 2.5 million tons of coal, about 5% of the combined output of all legal mines. Dad was 17 years old and working in the bootleg mine in 1936.

A special commission found 342 bootleg breakers, in 1936, one for every 5.7 “coal holes.” The average operation employed four workers each at $14 per week. Then-Gov. Pinchot told companies and the press that the “coal companies can at any time put an end to the production of bootleg coal by reemploying the men who are producing it.”

Again, a business decision, as labor costs were key and it wasn’t profitable to employ many in the mines. Profit over public welfare ruled completely, even back in 1936.

Incidentally, the term “bootleg” was primarily used for liquor during Prohibition. Some of the miners would be content if the public would just refer to miners as “independents.”

Nevertheless, Troutman points out that the Anthracite Institute circulated a pamphlet titled “Stolen Coal” at working collieries. The pamphlet at one time claimed that 20,000 men were bootlegging and selling four million tons annually, for a retail value of $32 million. If that were true, that meant bootleggers produced more than most coal companies.

The clash of private-interest capitalism and the quest for work and pay equality hit a high note during these times. Dad had many stories to tell, some of which were lost to the sands of time, yet had better fortunes after he left the coal-mining industry, fortunately.