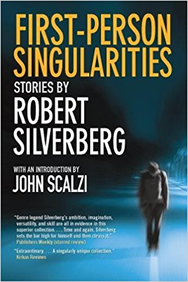

FIRST-PERSON SINGULARITIES

by Robert Silverberg

Three Rooms Press

(www.threeroomspress.com)

2017, 430 pp., $19.95

ISBN 978-1-941110-63-8

Click here to purchase

In Robert Silverberg’s story introduction to “The Dybbuk of Mazel Tov IV” in FIRST-PERSON SINGULARITIES, the author writes about submitting the story to Jack Dann, himself Jewish, as is Silverberg, for an anthology on “Jewish science fiction” to be called WANDERING STARS.

I find many of Silverberg’s comments amusing and, at the same time, oh-so-puzzling in FIRST-PERSON SINGULARITIES.

Especially when he writes: “I had written a Catholic science-fiction story not long before -- “Good News from the Vatican” -- and had won a Nebula Award for it, and I’m not even Catholic. I don’t think you have to be Jewish to write science fiction on a Jewish theme, either, but I did happen to have some familiarities with matters Jewish.”

OK, Mr. Silverberg. I was raised Catholic. I think “Good News from the Vatican” received a well-deserved Nebula Award, a beautiful, poetic tale that resonates with me to this day. And the technology is getting better to make this oh-so-possible. I don’t want to spoil it for those who haven’t read it.

But after all, Jesus was Jewish.

What puzzles me is, this late in the life of an SF professional who is writing close to 65 years, is why do we have what Silverberg himself called, in the introduction, “balkanization” of the genre? At this point, I don’t make any of those distinctions, and I don’t care whether the author is male, female, black, white, Asian, Jewish, Catholic, Protestant, Hindu, Muslim, etc. Personally, anymore, I would make no distinction in my enjoyment of a story or two from a black Asian Muslim transgender or a white, eastern European, male heterosexual. The only difference is the quality of the story they write. It is the only difference.

We are all authors, to some extent, and readers. How as SF fans and readers, with the homogenization of humanity and aliens everywhere we look, can we possibly think of balkanization? I may as well refer to myself as a white, male, heterosexual, southeast Pennsylvania writer.

Does anybody care anymore? Don’t we just want to read good SF?

Maybe a publisher should print an anthology about white, heterosexual, North Atlantic, Catholic males and leave it at that. Who knows what interesting stories I could tell? Or perhaps bore somebody else senseless with.

The intent of this single-author collection is to provide stories that feature the main character accounting for what happens to him or her in a series of memorable experiences with the cosmos.

In “Ishmael in Love,” Silverberg tests our deep-set understanding of the species called dolphins. Are they intelligent? If so, to what extent? And if they are, to a large degree, what happens when the brilliance of one such dolphin, Ishmael, working as a clear-water technician (foreman of the Intake Maintenance Squad on St. Croix) begins to feel affection for a human, supervisor Miss Lisabeth Calkins? What can it be but misunderstood, unrequited love?

What to make of an aberrant and rascal computer in “Going Down Smooth”?

In “The Reality Trip,” a cretaceous being, living in human disguise in a New York hotel, knows he is not alone, even if he feels so lonely off-world; he knows only of Swanson, another of his kind, living in the same building. But life really gets interesting for the cultural anthropologist, surviving in human disguise on a world that is 90 light-years from his own home, when he meets an obsessive poet, Elizabeth Cooke.

(Silverberg seems to love the variations of Elizabeth: Lisbeth, Beth, etc. in many stories.)

Elizabeth is determined, in a fatal-attraction-like way, to open the alien’s mind to human love, even if he is an alien. But what of his mission? In the end, does love truly conquer all?

In “The Songs of Summer,” Chester Dugan, a man who is transported out of a 1956 New York subway station to a place, unknown in the 35th century, meets Kennon and Dandrin and a host of other survivors of The Bombing, all trying to rebuild civilization. In this era and place, so much of the 20th century, its customs and uniqueness, was lost. Or was it?

In “Push No More,” a gawky, adolescent schmuck, Harry Blaufeld, is hot for Cindy Klein. Harry is a superman: He has telekinesis. He can poltergeist (push objects around with his mind) and is happy about his real powers. This is the story, no doubt, that inspired Silverberg to write about David Selig, the telepathic mind-reader of Silverberg’s most famous novel, DYING INSIDE, written at nearly the same time, from the early 1970s (DYING INSIDE was published in 1972 by Charles Scribners Sons). It shares much of the same from Selig’s universe. Perhaps too much of the same.

In “House of Bones,” a time traveler is stranded in the past, in about 20,000 BC. He must learn the customs and language of a tribe and to hunt the “ghost,” who turns out to be a Neanderthal. The traveler longs for home, but can he return? At any rate, for him, what is “home?”

In “Our Lady of the Sauropods,” Anne, a researcher who visits the L5 dinosaur island in orbit over Earth, becomes stranded and must learn to survive. “Dino Island” is a 500-meter orbiting Jurassic Park-like laboratory where many species of dinosaur have been genetically resurrected. Eventually, Anne learns to survive and soon discovers her fate is not tied to disaster, but devotion.

In “There Was An Old Woman,” an experiment in procreation and determining the life and career makeup of dozens of cloned boys doesn’t go quite as expected for one woman.

“In the Beginning I Kept.” In this tale, exactly what is accepted as beauty? Or is beauty simply what is most popular?

In “Passengers,” aliens invade earth by “riding” on the consciousness of others. Can life, and those who seek love, ever be normal?

“The Science Fiction Hall of Fame” is a tale that is part autobiography. It all happens before Silverberg’s first official (of many) retirements. You see, he has been worn down by two decades of writing SF, and explores, via a broken plot storyline, a lot of SF’s tropes, switches and buttons, yet speaks about an author’s craving for transcendence.

This collection also includes “The Secret Sharer,” an homage, SF-style, to Joseph Conrad’s tale.

In “To See the Invisible Man,” in a society that punishes insensitivity, making it a crime that turns people invisible, what becomes of someone who shows compassion for the condemned?

This collection of mostly classics is worth every penny.